I (Lucas) am on a trip to Europe, mainly for family reasons. While I’m here, I decided to take the opportunity to visit some folks TLC has been working with for a while.

This is Raja Appuswamy, a data scientist who’s been leading the “synthetic DNA” component of our collaboration. Raja lives in the south of France, and it so happened that my family was passing close to his town, so we met up for a gelato in Nice.

In this photo, Raja hands over a plastic vial containing four tiny stainless steel capsules of synthetic DNA. The DNA in these capsules houses a prototype version of our Horror Film 1 Users Manual.

The proposition is this: synthetic DNA can store vast amounts of data, without loss or degradation, at room temperature, for 1000 years. For this reason, Raja argues, synthetic DNA may be a good candidate for archiving items of cultural significance. It’s early days for this technology – using synthetic DNA is still too expensive to be properly useful – so really, our collaboration thus far stands as a ‘proof of concept’ and a provocation.

(At the bottom of this blog post, I’ve listed a bunch of links with further details about the project.)

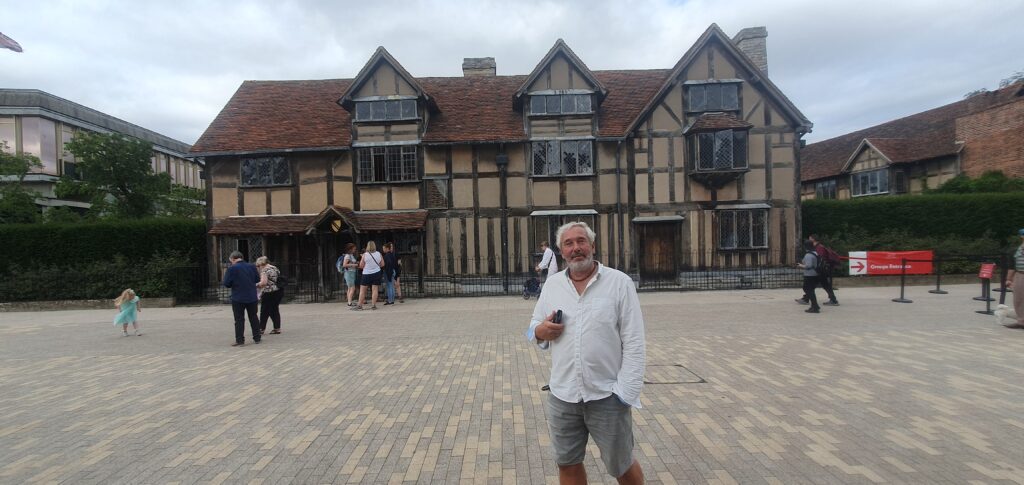

After France, I went to England, where I finally got to meet Oliver Le Grice in person. Here we are together at last:

Oliver is the son of Malcolm Le Grice, who died in late 2024. Louise and I have been working (via Zoom) with Oliver and Malcolm for the last three or four years. Together we have been learning all we can about Horror Film 1. We’re making a Users Manual which will enable us (and others!) to continue performing and experiencing the work in the future.

This project has been a big learning curve for Oliver. For a long time, Oliver was an industrial designer in the automotive industry. Over the last five years, he’s also been assisting his dad to organise and archive his considerable body of artwork. In the process, Oliver has become more aware of Malcolm’s creative philosophy. Our Zoom calls have helped Oliver develop this awareness, and deepen his connection to his dad.

Oliver lives in Stratford Upon Avon – the town where Shakespeare was born. After we had lunch with Oliver’s mum (and Malcolm’s wife) Judith, we had a stroll around the town. The town really trades on Shakespeare’s fame. Without Shakespeare, perhaps Stratford Upon Avon would be just a quaint and pleasant old country village. But the Bard’s connection means that 2.7 million visitors come each year. A clear example of an artist-led economy!

In the above photo, Oliver and I pose for a selfie in front of a cafe housed in a building dated 1485. This was built when Shakespeare was about 20. These days, when I encounter “ancient stuff” like this 540 year old building, it makes me think of Raja’s provocation – that synthetic DNA could potentially store and transmit cultural data for 1000 years.

(I write “ancient stuff” with inverted commas intentionally. All around Europe, tourists flock to see stuff which is somewhere between 200 and 2000 years old. In Australia, the “built environment” is not as old. But cultural landscapes maintained by Traditional Custodians in Australia are much much older than any buildings in Europe. As non-indigenous artists, we can learn a lot from the practices of custodianship used by Aboriginal communities – the idea that one’s responsibility is to keep culture alive, to maintain it – but not to “own” it. More on this perhaps in a later blog post!)

How is it that Shakespeare, 500 years after his time, still has ‘currency’? Many (perhaps most) pieces of cultural production (art, architecture, music, plays, poems, performances, folk art practices) from the 1500s have long since disappeared. By definition, we only encounter the survivors of this process of ageing and attrition.

Shakespeare still has cultural (and economic!) currency because his plays are regularly enacted, performed, and experienced. It’s not enough to just “archive” the texts of his plays in a secure box for safekeeping. The plays need to be “used” (and re-used). (Louise Curham writes about this idea of use as essential for archiving in her Phd).

Unique versions of Shakespeare’s plays become useful within diverse contexts – these are often called ‘adaptations’ of the work. Each is different – they have evolved – and even so, each iteration is “the work itself”.

Traditional performances are staged by communities who choose to value this kind of “authenticity”, while radical variations are staged in contexts where it’s desirable to translate Shakespearean themes into contemporary situations. It’s the combination of traditional performances and new adaptations which keeps “Shakespeare” alive. His work is thus regarded as continuously relevant, evolving alongside broader cultural contexts over hundreds of years.

What does this have to do with our work with Horror Film 1? Well, we want to keep this artwork alive. We don’t believe it’s enough to get all the documentation and archive it in a secure box for safekeeping. We have been striving to make the work available as a performed experience. Raja’s synthetic DNA capsule gives us the enticing opportunity to send a “telegram” 1000 years into the future – a kind of time capsule. But we cannot rely on this sort of static safekeeping alone. The work also needs to be regularly performed, and, ideally, adapted to new circumstances and contexts.

Last year we met Louise Lawson (LL) from the Tate, who is involved with the conservation of live art and performance. (I call her “LL” here to distinguish her from Louise Curham). LL has a similar philosophy to ours – that performative art works needs to be regularly “activated” in order to be kept alive. Here’s a nice description of LL’s approach, from a participant in a workshop that she led a few years ago in Melbourne:

Unlike static artworks, performance works, like other time-based artworks, need to be activated for their care and documentation. Thus, it is important to acknowledge that the documentation, however comprehensive it might be, is not the work itself. The work inherently incorporates what [LL] calls ‘a process of doing’ and an embodied form of knowledge that is distinct from textual knowledge.

[Here’s another great post about LL’s work with Tate].

Thinking about all these meetings and encounters, it occurs to me that our desired contribution with this project is threefold:

- To keep Horror Film 1 alive into the future – allowing it to adapt and evolve beyond its origins;

- To contribute methods and philosophies of practice to the developing field of live art archiving and conservation;

- …and (thanks to Raja’s DNA capsules) to ask some fun speculative questions about the transmission of culture into the far-far distant future.

Some relevant links:

- Blog post about creating “users manuals” for works of expanded cinema

- Our current user manual for Horror Film 1 (1971) (NB – this is in google doc form, including comments – this is continually evolving)

- Same as previous, but in static printable pdf format (eg for exhibition in galleries)

- “Expanding into the future: Cultural heritage as a use case for Synthetic DNA storage + transmission” – a speculative research proposition

- Our short academic paper about this project submitted to the 2024 International Symposium of Electronic Art.