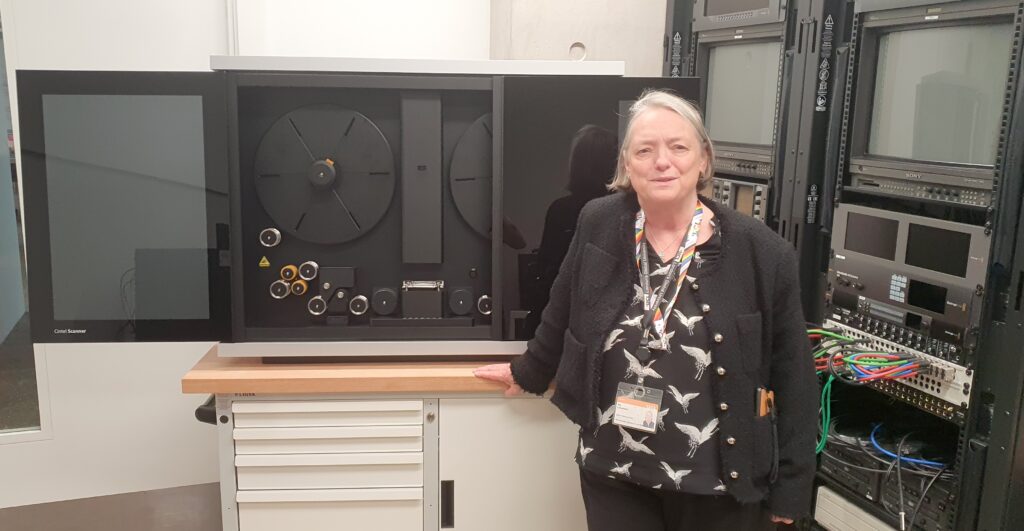

While in England, I (Lucas) was lucky enough to visit Pip Laurenson and Libby Ireland at University College London. They have a whole program which tackles the philosophical and practical challenges of conserving media art and performative art. In the photo above, you can see Pip showing me a very fancy celluloid film scanning device, used for transferring 35mm or 16mm films to high-resolution digital video files.

In the same room (I wish I had taken a photo!) there was a pile of sample video formats – ranging from U-Matic, Beta, VHS, mini-DV, DVD etc. One of the big questions for the conservation of moving image work is when and how to transfer from one format to another – and the aesthetic considerations of such transfers.

With conservation decisions about media artworks, there aren’t really any right or wrong answers – much of this is done on a case-by-case basis. A lot depends on the artists’ stated intentions, alongside experienced judgements about the most important things to prioritise about a particular artwork (Louise and I refer to these as the work’s “DNA”).

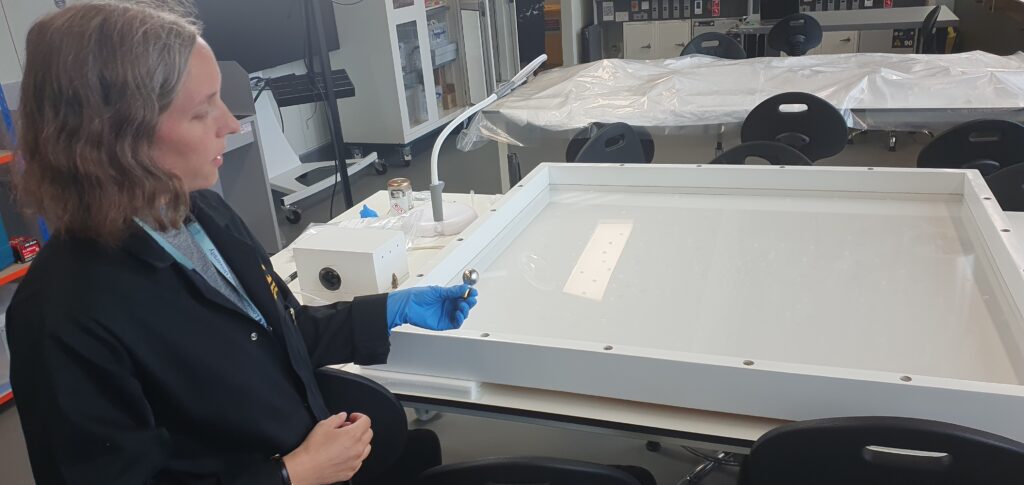

In the conservation lab at UCL, Libby showed me this artwork by pioneering kinetic artist Liliane Lijn. It’s called Cosmic Flares III (1966).

Courtesy Liliane Lijn, Rodeo London, Piraeus. © Liliane Lijn. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2021. Photo: Stephen Weiss/ Liliane Lijn

The work consists of a painted timber frame, a perspex panel with a pattern of dots made of small polymer lenses (a bit like contact lenses for your eyes), and a set of incandescent light bulbs set into the frame edge. The light bulbs turn on and off in different combinations to create an ever changing kinetic light sculpture.

The light bulbs were very specifically chosen for the work, which was made in the 1960s. Of course, these bulbs are no longer commercially available, so the challenge for the conservator is to work with the artist (who is still alive), the collector who owns the work, and various lightbulb manufacturers to come up with a solution. Possible solutions could include:

- to commission the fabrication of bespoke incandescent lightbulbs to match the originals;

- to reverse engineer the bulbs so that they have the same outer shell but with an LED insert;

- to start from scratch and remake the whole artwork with new bulbs;

- to try out some other solution.

In the end, what decision is made will depend on a range of overlapping factors:

- how flexible the artist is in allowing the work to evolve into new technological formats;

- how expensive the new lightbulbs are (and how much the artwork’s owner is prepared to stump up);

- the quality of light that any replacement bulbs have, relative to the originals;

- and what “meaning” those specific bulbs had in the original work.

There are a lot of factors and the solution is always going to be an experiment, and an opportunity for learning.

While we (Pip, Libby, and I) were talking, we reflected on the fact that the practice-based research processes underpinning conservation are dialogical – they involve a lot of conversations, and these conversations can generate fascinating stories which, if shared with an audience, can enrich our experience of the work. That’s why it’s great that Pip and Libby are so diligent in publishing the stories of their work in collecting and conserving new media and performance art. You can see some of their articles here and here.