In the early days of Teaching and Learning Cinema (when we were known as SMIC – Sydney Moving Image Coalition) we carried out some very (shall we say) “experimental” re-enactments of works by VALIE EXPORT, Takehisa Kosugi, Annabel Nicholson and William Raban.

These re-enactments were really groping around in the dark, but they set the scene for our more thorough activities later on.

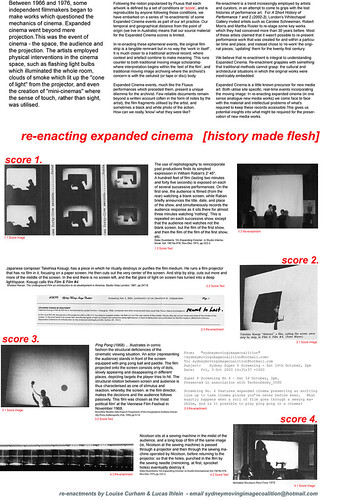

Here’s a poster we made in 2004 describing our approach to these works. This poster was presented at the presented at the Association of Moving Image Archivists conference in the US in 2004 (AMIA):

Click on the image below to see a larger version:

And here’s some of the text from the poster:

RE-ENACTING EXPANDED CINEMA [or history made flesh]

Lucas Ihlein and Louise CurhamMoving image traces in expanded cinema are much closer to traditional archival records where context and artifact combine to make meaning – the construction of history takes place in this zone. This runs counter to traditional moving image scholarship and the traditional concerns of moving image archiving where interpretation begins within the text of the film and the archivist’s concern is with the celluloid (or tape or disc) body.

We identify two main strands in expanded cinema, spectacle and deconstruction. Both these strands were ultimately a critique of traditional cinema with its rigid apparatus. Both embraced a cinema beyond the frame where the artifacts of the celluloid strip and the projector formed only part of the equation. Essentially expanded cinema was the event of cinema – the space, the audience and the artifacts (or the implication of the artifacts (e.g., Long Film for Ambient Light, McCall). In recreating these ephemeral events, the moving image element can only be a trace of the event itself.

In practice, for us here in Sydney seeking to recreate work from 30-40 years ago made in Europe and in the US, distance from the source give us license. Our access to primary sources is absolutely limited – although there was some expanded work made in Australia, it’s barely documented and certainly not archived (a situation we’re trying to change). So in practice, our source material, the scores, have been printed materials. Our use of published ‘scores’, readily available in the public domain, is part of our artistic agenda with this work – we see this as a reflection of the open work ethos of the form in its day.

The scope for re-enactments that actually have access to original materials and thorough documentation would be incredibly interesting. In a sense this kind of work is very much like performing a musical score – both purist re-enactments and contemporary interpretation are equally legitimate. The slippage in the actual embodiment of the work and what’s known about it is to us the most interesting element. This is the difference between simply viewing documentation (printed or time based) and actually attempting to recreate or restage the work.

The lessons in all this for moving image archivists are: the traces of moving image works are wider than just the moving images themselves; documentation of place, time, space, and audience are all helpful; direct connection from expanded cinema to new media works where the hardware is ephemeral and shapes the work but is often only one element to the work. In the realm of digital media, where re-enacting the digital string over time presents a more realistic possibility, grasping and indeed archiving the context of the event becomes doubly important to meaningfully reconstituting it.