Today Adit from Lab Laba Laba is going to make a performance of Horror Film 1. The performance is happening in the Big River film meeting organised by Richard and Dianna of Artits Film Workshop/Nanolab, leaders in the artist-run film labs community. Tonight’s performance is happening in the old paper mill in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, day 4 of this extraordinary gathering of film lab members and film maker-artists from all around the region. Check out the attendees list and you’ll see people from Taiwan, India, Australia, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, China, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Japan …

So that’s the background.

Why Adit, why in Kanchanaburi

Last year, I met Adit in Solo in central Java but I knew about him before that because Richard told me about the artist-run project he is part of Lab Laba Laba. When we met, we discussed doing some film performances by exchanging instructions. This is our chance to bring at least some of that conversation to life as tonight Adit will use TLC’s manual for Horror Film 1, Malcolm Le Grice’s performance from 1971 (find the manual/Google doc here)

Reflection on conversations on Days 2 and 3 (Thurs/Fri)

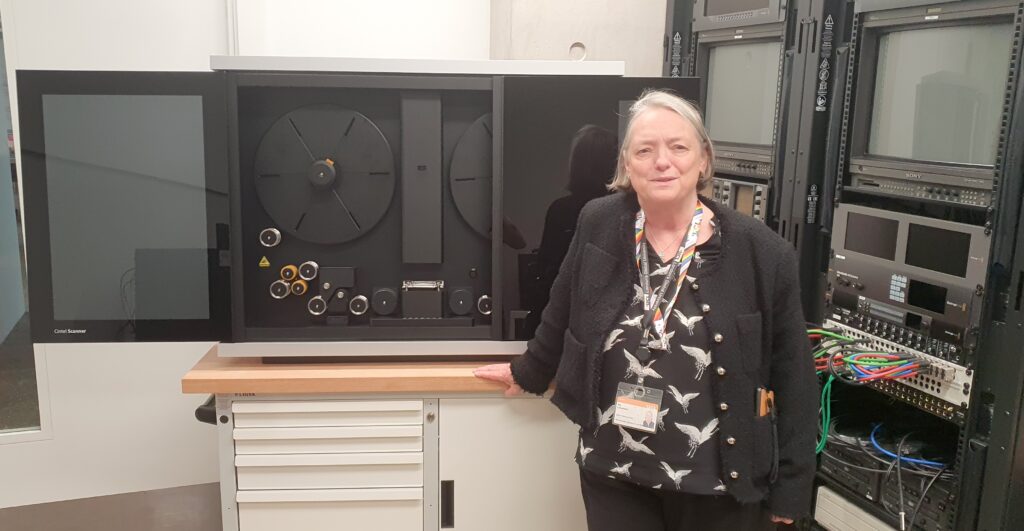

Above: Adit and Louise discuss the manual at the Motorcycle Warehouse, a key venue for Big River in Kanchanaburi.

No prior knowledge

Adit has learned about Malcolm and HF1 from our conversations. This performance will be very much how I imagined future users would engage with the manual, not much time to prepare, for a particular event like a festival or screening. This is a good test for the manual. Adit does make expanded cinema himself, here’s a still from his performance on night 3 at Kanchanaburi. So he brings experience as a performer.

Here are some points Adit raised.

More context/contact with Malcolm

Adit felt the instructions from Malcolm in the manual are conversational. Initially Adit said he wanted to make his own version of the instructions so he could make sense of some of Malcolm’s comments for example what does Malcolm mean by the spirit of jazz? What is Malcolm’s understanding of jazz? Initially I thought Adit meant he wanted something more like a list or a recipe for how to perform the work – not the case, he felt that information was there but it was more context for Malcolm or more insight into Malcolm that was missing for him.

We visited the venue on Friday morning, an abandoned 1920s paper making factory, lots of big tan worn walls. Lynn Loo was also at this meeting of film artists, the plan was that she would perform in the same space as Adit, later in the program. Lynn, Adit and I had a chat about understanding Malcolm. I brought up the recording of the first zoom call we had with Malcolm with Oliver (Malcolm’s son) and Jed Rapfoegel from Anthology Film Archives. I could immediately see why it was so helpful to Adit to hear and see Malcolm speak about how he feels about his films and his practice, the section we watched is close to the permission/invitation in the manual. Adit reported this was

Adit makes performances but he’s not a performer

Adit explained that he does make expanded performances but he doesn’t use his body in them in the way he will need to in HF1. This led to a useful conversation about the walk being a procedure, that it’s not so much a performance as carrying out an inquiry into the relationship between the body shadow and the projections during the walk from the screen back to the projectors. This distinction between it being a performance and a procedure seemed helpful for Adit. We also discussed the choices by other performers – Nicci Haines, Lucas, Cinzia and Betija and had a look at the HF1 log book to check Cinzia’s notes.

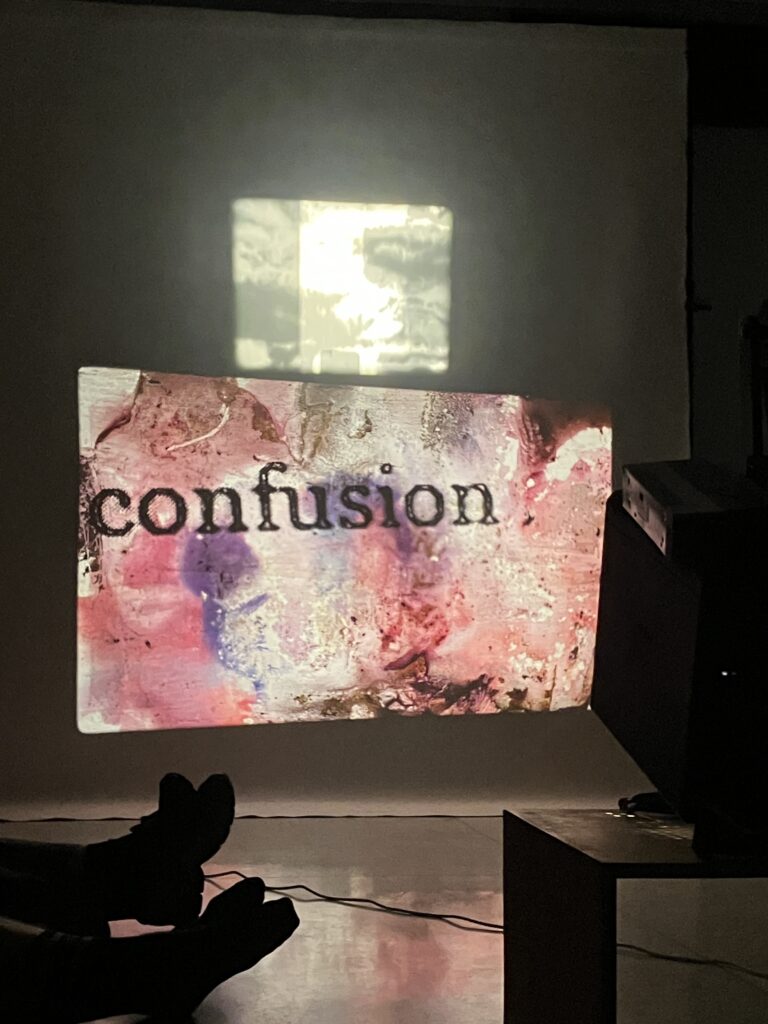

Here’s an image from Adit’s performance on Friday night in the Big River program.

Adding content or not

In the first conversations Adit returned a few times to Malcolm’s words about the performance being ‘up to you’. Adit initially explored ideas like making the projectors move or bringing in more performers in the second half of the walk. By Saturday he was clear he was going to use Malcolm’s instructions as faithfully as possible so that the audience could see Malcolm’s HF1.

My role

At the hotel before we went to the venue on Saturday, we spent time talking and looking at loops (nongkrong/hanging out in Indonesian). Lynn Loo was with us for some of this and Film Nerve from Singapore passed by – here are Mark and Li Shuen in the background as Adit and Lynn look at the loops.

Adit and I discussed my role. He concluded the best word for my role was ‘consultant’. In the program the performance was billed with both of us named. That’s something to think about in the future. Is that correct?

When we visited the venue on Friday morning and we checked out that Malcolm Zoom call recording, some other things came out in conversation.

The walk is procedural rather than performative. From my experience, you’re looking to find the shapes and give them time. For me, my curiosity about the shadows and the projections is what is driving my performance. It’s quite measured and quite slow. Adit was worried about the duration – I feel that it sorts itself out because you end up exhausting/or getting to the end of what you can do with the projections.

Early on we discussed clothing etc. Adit felt that the nudity issue is a distraction and not really on topic for what is important about the work – the shadows, the body and the projectors but he did appreciate Lucas’ point that it makes the performance a ritual. He felt the inside out t-shirt was the best solution. It worked really well.

After the performance – some reflections

The performance was terrific, Adit was composed and solved the ending really effectively, getting below the projection beam and defocussing, turning off.

Loops

The loops may be on the pale side, these are the Niagara prints. Cinzia Nistico, an artist from Italy has been making very successful performances with her colleague Betijia over the past two years. You can read some of Cinzia’s notes in the manual performance log book here. Cinzia has the loops from Niagara’s first print run which were very pale. She and Betijia resolved this by adding filters to the projectors. This set of loops Adit is using is a different print run with more colour but they are still less dense than how I remember the original.

Lucas and I have begun the dialogue to either re-print Love Story to get a new set of loops or remake the loops in a printer. I think I am favouring re-printing Love Story but let’s see.

So while the Niagara loops are not ideal, I believe Adit’s performance was not compromised by this because the key visual effects of HF1 were present but I expect stronger prints would make it more ‘wow’.

Our set-up time on Saturday didn’t allow time to test in performance conditions – we were first on the bill at 630 and dark fell at 615 so there was not time to explore filters. That would be good to follow up with Cinzia.

Audio

The audio was my breathing track from 2014 streamed into a PA. Adit reported it was a bit quiet for him, midway through he felt he couldn’t really hear it.

Projectors too close

There were limited table and stand options. We used one table for the three projectors. I believe they were a bit close together as the ‘jump’ across frame created by the overlapping projectors was present but subtle. So that surface fitted the three comfortably but with no lee way – it was about 140 cm long. The challenge is to separate them but not introduce keystoning to the overlapping projections on the wall. So it was probably 10-20 cm separation we needed so totaly length about 180cm.

Choose the loops before hand

We spent quite a bit of time finding the right loops with maximum density and minimal scratches (the scratches from our used loops are printed in to the Niagara material). I should have just organised those loops ahead of time. As Adit said later, if you had lots of time, it’s nice for the manual user to do that process but we were short on time.

A paper version of the manual is needed to give to others

While we were setting up, I spent a lot of time talking to people, answering questions and showing them drafts of the manual. A hard copy is really wise for this. Folks can then learn what’s going on but the manual user can keep working. The QR code is useful in the manual for this too.

Early checks in the set up

Is the surface you will project on okay – check the film will show up sufficiently on the wall, think about obstructions or objects on the wall – we had a few, we decided they were fine eg old metal fixtures.

Is the projector height okay – you need to check where your body will be in the projection when you are at the wall and what your shadow does as you come closer. We started out too low and Adit’s body would have filled the frame rather than his hands etc. The starting size is less important but it’s good if at least some of your torso is in the projection.

Is the throw okay? Zoom lenses needed on all projectors? It’s easier with three zooms, you do need at least one zoom for the large image.

Test the loops – are the colours working together okay? As above, a bit of a problem with the current Niagara loops. Remember the Niagara loops have scratches printed in. I got all fussy about this before I remembered those are printed in.

Manual as Google doc, video, paper

Later I talked to Shinkan Tamaki about the manual and he asked if there was a video version. I explained we had made a series of explainer videos but we hadn’t used them yet. I also mentioned our idea of the AI bot where everything we have about HF1 creates a learning model/bot that you can consult to guide you. Re the video, I could see why Shinkan was asking that – there is a lot of text in the manual.

Talking with Adit later, he felt the text was good because it gives the user room to move because you have the step of interpreting the text. He thinks that room to move is really important. If it was a video, it’s a lot more precise and you’d feel you must do it this way.

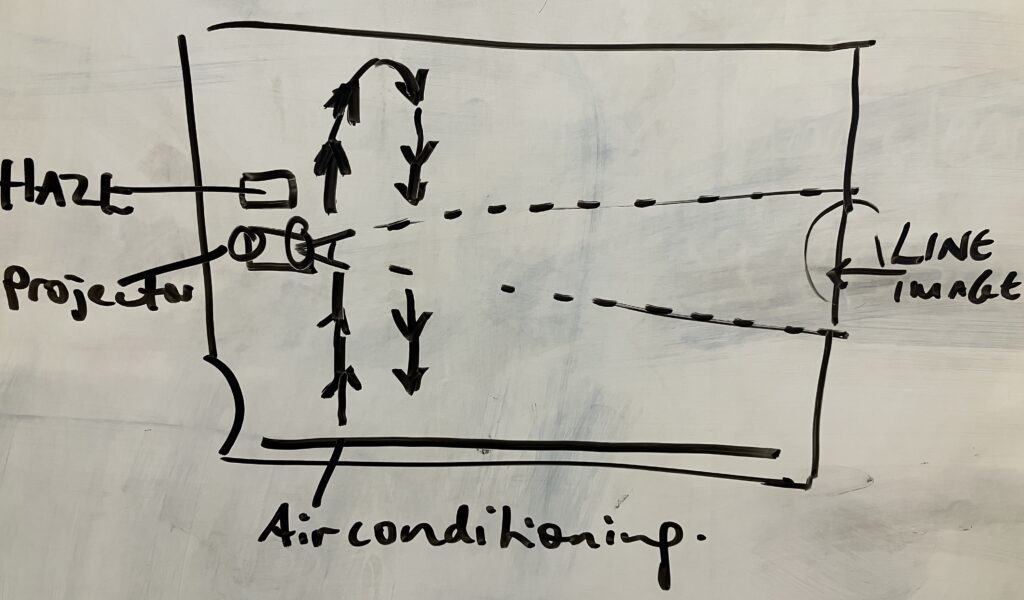

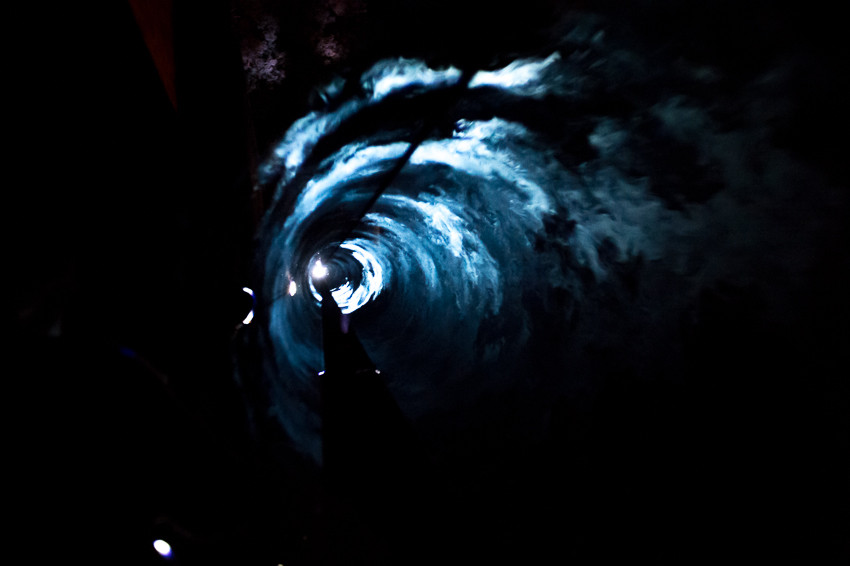

[Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973) presented at CEMENTA Festival in Kandos, 2015. Photo by Alex Wisser]

[Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973) presented at CEMENTA Festival in Kandos, 2015. Photo by Alex Wisser]