Lucas Ihlein: Mediating Experience in Expanded Cinema Re-enactment

The following is a contribution to ISEA 2013 – presented as part of this panel session.

The panel, organised by Brogan Bunt, was set up to address the broad notion of mediation – and to respond to his assertion that “artists themselves, in their practices, have begun to move fluidly between paradigms.”

“How,” Brogan asks, “does the experience of digital processes inflect work produced in the broader social field? How are issues of concept, process, event, participation and interaction remediated through intimate experience of digital media?”

I’ve attempted to answer these questions, in my rather folksy way, by thinking about the work that Louise Curham and I do as Teaching and Learning Cinema.

If you like, the text may be accompanied by a slideshow of images from our work in re-enacting expanded cinema:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/bilateral/sets/72157634073279851/show

Continue reading “Lucas Ihlein: Mediating Experience in Expanded Cinema Re-enactment”

After meeting Malcolm – top of mind

Notes in response to specific questions have been started by Lucas and we will continue them but it seems important to capture what’s stayed at the top of the mind after visiting Malcolm:

– we covered a lot of ground!

– Malcolm says that when he made these performance film works (eg Horror Film, Gross Fog, Matrix, 4 Wall Duration), his orientation was cinema rather than live art as we now think of it (eg performance art, happenings), the dialogue/position was with/against screen and film culture. This is true for his film works of this era too.

– in a conversation about the context for making his work around the time of Horror Film, Malcolm made the point that at the time and in the whole era, experimentation in media other than film drew upon long lineages. He used the example of music where things have seemed strange and new to makers and audiences many times before. As a young form, cinema didn’t have this lineage and so things really could be new in this form, energising and exhilarating in its newness, difficult in the lack of context and language for audiences.

– Malcolm advises that the first performance of Horror Film 1 (1971) was at Arts Lab – an interesting question because we found nothing about it in the files we have consulted to date at BAFVSC about Malcolm, Filmaktion and London Filmmakers Coop 1966-74.

– White Field Duration is effectively a scratch film where transparent leader is slowly marked with vertical scratches until it is evident they are intentional. Then horizontal scratches emerge. In the end the two fields of scratches seem to be rain over a body of water. The image is then reprinted in neg/pos. The sound is created by the image which runs into the optical sound track space. We understand from Lux that as Malcolm told us, there is just one print of this and no neg.

MLG Questions 01: Breath

When we started thinking about re-enacting Malcolm Le Grice’s Horror Film 1 a year ago, several questions popped up straight away.

These were mainly technical issues about the source material for the three colour projections, and how the audio is produced while the piece is being performed. Some of these questions were answered by Malcolm here – but it’s only now that we’ve spent several days hanging out with him that we begin to understand these answers.

Bit by bit, I’m going to flesh out some of the answers based on notes that Louise and I made while we were in Devon…

THE BREATHING SOUNDTRACK:

Our instinct was that the amplified breathing which provides the sonic undertone of the work would be produced live – a live feed from a lapel microphone, for example. This would seem to fit with the live-ness of the projected shadows produced by the body in front of the three projectors, and could operate as a kind of index of the performer’s own physiological state (calmness, exhaustion etc) during the performance.

Continue reading “MLG Questions 01: Breath”

TLC Public Events, June 2013

Louise and Lucas are busy this month.

Here’s what’s happening:

Wednesday June 12, 4-5pm

ISEA, New Law School Lecture Theatre 106, University of Sydney

Lucas is presenting (via Skype from London), speaking briefly about our work re-enacting Expanded Cinema from the point of view of medium and materiality. You can read the abstracts and the panel synopsis here.

Friday June 14, 2:30pm-4pm

Institute of Education, 20 Bedford Way, London WC1H 0AL

Lucas and Louise will be performing (Wo)man with Mirror and engaging in discussion afterwards, at a conference in London. The conference is called “Museum Futures in an Age of Austerity” and the details are here.

Here’s the draft conference schedule.

Tuesday June 18, 7pm onwards

Apiary Studios, 458 Hackney Rd.

Louise and Lucas are performing (Wo)man with Mirror and engaging in discussion afterwards, together with Dr Patti Gaal-Holmes & Dr Kim Knowles. Guy Sherwin “himself” will be there, along with his partner and collaborator Lynn Loo.

All the details are here.

This event was kindly organised by Sally Golding and is an Unconscious Archives Salon.

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, with support from ACME studios in London. Here is a flyer from ACME studios as a PDF.

Wednesday June 19th, 7.30pm onwards

Cafe Oto

18-22 Ashwin street, Dalston, London, E8 3DL

Tickets : £8 adv / £10 on the door

Louise Curham will be showing her handmade super8 films in collaboration with musician Alison Blunt. The evening also features the work of Karel Doing and Pierre Bastien. This event is number 8 in the Unconscious Archives series organised by Sally Golding and James Holcolmbe. All the details are here.

What are we doing in England?

Here we are with Malcolm Le Grice in his studio in Devon.

Louise Curham and I have come to Devon, complete with a big and patient entourage (our families!).

We’re here to visit Malcolm and begin the process of working towards a re-enactment (or an intergenerational handover of sorts) of his Horror Film 1 from the early 1970s. (Here’s a blog post from a year ago where Louise and I ask some questions about this piece and what re-enacting it might involve. And in this page, you can see what we mean by “re-enacting expanded cinema”…)

Malcolm still performs this key work of expanded cinema – in fact there’s been a resurgence of interest and lots of requests for him to do it, ever since the turn of the century.

But in 2010 when Malcolm came to do a screening of his work in Sydney, we started a conversation about his feeling that it might be time to think about turning it over to someone a bit younger. In fact, as early as 2001, he was talking about the need to find an “understudy”:

[source: Malcolm Le Grice, Improvising Time and Image, essay in Filmwaves 14, 2001, p. 14-18]

This project has flowed from the work we did re-enacting Guy Sherwin’s “Man with Mirror”. Our re-enactment of Guys’ piece was first performed in 2009, and we’ll present it in London for the first time very soon – details here.

The Horror Film project, of course, has a range of different challenges and we can’t pre-empt how we’ll resolve them before we jump in and start playing with the work using our own bodies.

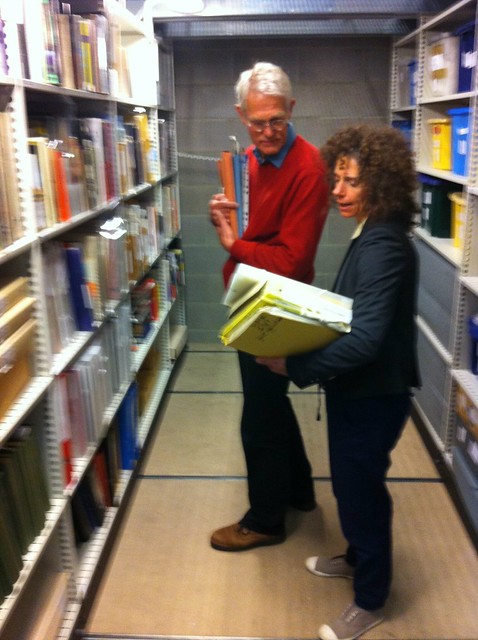

However, even before we start, we’ve been really enjoying talking through a whole range of practical and philosophical issues with Malcolm in his studio in Devon – and we also spent some fun days with Steven Ball and David Curtis, in the archives at the British Artists Film and Video Study Collection at Central St Martins College in London.

Here’s Louise in her element rummaging through the compactus with David Curtis, who is the lynchpin of this very important archive:

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body, with support from ACME studios in London.

Artists’ Salon: Moving Image 1 at Critical Path, Sydney

Part of Critical Path’s Artists’ Salon series, Moving Image 1 looks at experiments with movement within interdisciplinary practice and is curated by Narelle Benjamin and Sue Healey.

It will feature a discussion with and studio presentations of work by artists Sam James (From the Rainforest Mind to the Desert Mind) and Louise Curham and Lucas Ihlein ((Wo)man with Mirror).

Saturday 11 May, studio open from 3pm onwards with 4pm event start.

Free event, but please RSVP here.

More details:

CRITICAL PATH PRESENTS

ARTISTS’ SALON: MOVING IMAGE 1

installation works by Sam James, Louise Curham and Lucas Ihlein

SATURDAY 11 MAY 2013

4.00 – 6.00 pm

at THE DRILL

1c New Beach Road

Darling Point (Rushcutters Bay)

The Drill Hall will be open from 3.00 pm for viewing of Sam James’ installation.

Free public event

Continue reading “Artists’ Salon: Moving Image 1 at Critical Path, Sydney”

TLC Malcolm Le Grice Screening in Canberra

From the archives – Sydney Moving Image Coalition screenings 2003-4

Screening #1 Lanfranchi’s, 18 Mar 2003

Screening #2 Lanfranchi’s May 2003

Screening #3 Lanfranchi’s Jul 2003, #4 Kudos Gallery, COFA late 2003 (page 1, page 2)

About Primary Sources and the 2004 screenings (page 1, page 2) – a manifesto!

Screening #5 Lanfranchi’s 3 Feb 2004 inc. Takehisa Kosugi’s A Film & Film #4. (Side 1, side 2 of A4, triple folded)

Farewell Albie Thoms

Australia has lost a legend of cinema.

Albie Thoms’ obituary appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald yesterday. And another one from ABC MovieTime.

From the Herald piece by Philippe Mora:

Never bowing to overtly conventional cinema, this modest, knowledgeable and catalytic artist absorbed the history of the avant garde in Europe and became a lifelong avant gardist himself, with a uniquely Australian taste.

Before funding was provided to some filmmakers by state and federal government, Thoms and his mates, like Bruce Beresford, Garry Shead, Aggy Read, David Perry and others, grabbed 16-millimetre cameras, trekked into the landscape and aggressively started filming. The critic Charles Higham immediately praised the first films. This resulted in an uncensored Australian cinema in aesthetic and moral synchronisation with a worldwide ”underground” film movement.

If you can, get Thoms’ book Polemics for a New Cinema – it’s a terrific chronicle of alternative cinema in the 1970s.

Danni Zuvela did an extensive interview with him, back in 2003, on Senses of Cinema. Here he is, reflecting on the development of a proto-expanded cinema / light show event:

The Ubu lightshows grew out of the happenings staged as part of “Theatre Of Cruelty.” In one of those we projected a film over an actor being disrobed as he recited a poem. The interface between moving actor and moving film image was fascinating, and recurred when we projected films over rock bands. Then the bands began reacting to the films, resulting in improvisations between musicians and lighting operators, and soon we were making films expressly for such performances, scratching and handcolouring black leader and painting onto clear leader. Eventually they were projected on the audience as well as the musicians, creating a mass performance (in one case with 4000 people) in which cinema had expanded to fill the room.

I leave you with this piece from Jim Knox, reflecting on Thoms’ film Marinetti… as Knox says, “not for the puny lobed”!